Hannibal's Black Schools

DOUGLASS SCHOOL, NAMED FOR FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Educated slaves posed a great threat to their white masters. Aside from offering them greater opportunities for escape, literacy also allowed slaves to communicate secretly with each other, leading to potential slave revolts. Consequently, slave states passed laws that made it illegal to teach a slave to read or write. An 1847 Missouri Constitution law prohibited blacks, slave or free, in Missouri from being taught to read or write. Any person caught teaching an African American to read or write faced a penalty of a $500 fine or six months in prison.

At great risk, Rev. Oliver H. Webb, a free Black minister, encouraged other free blacks in the Hannibal community to save what little of their hard earned wages they could with the hope of building a school. In 1853, the free black community purchased a few plots of land at the corner of Center and 8th Street for $37.50. On this land, they built the first one-room schoolhouse, which also served as the African American church on Sundays. Students, young and old, paid $1 a month to learn. Some of the school's earliest teachers included future Senator Blanche Kelso Bruce. Before emancipation, African Americans committed a monumental portion of their meager resources to establishing and operating schools.

Supported by the Hannibal Public School System, the segregated Douglasville School opened in 1870. This three-room, wooden-frame building, located in Douglasville (named for Joseph Douglas) at 925 Rock Street, served as the first officially sanctioned school for African Americans in Hannibal, though the community-created school had existed since 1853. Overcrowding required construction of another colored elementary school. The Lincoln School, located at 1068 Fulton Avenue, was built shortly thereafter. In 1874, under protest, the Hannibal Public School System finally hired its first African American staff, among them Joseph Pelham, principal and Ella Gordon, Jenny Golden, and Meta Pelham were the first colored teachers.

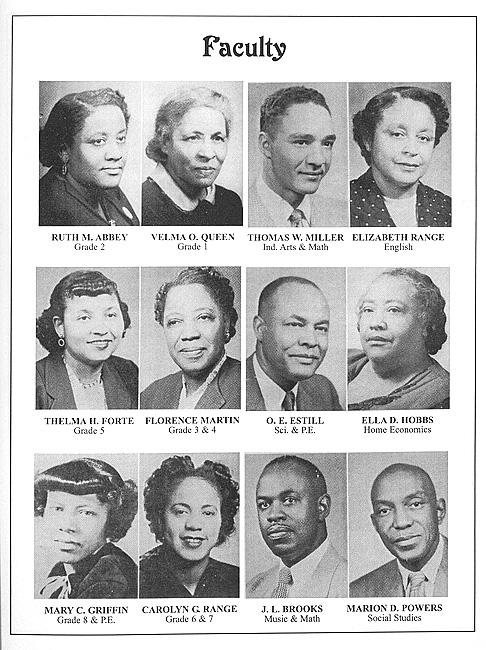

Douglass School opened in 1885, it included a high school designed to meet the needs of all African Americans students in northeast Missouri. Black students traveled great distances to attend the school, some coming as far as 50 miles to attend the only "colored" high school available to them. The eight-room brick structure employed African American teachers and administrators. In the Jim's Journey museum, visitors can see yearbooks from the Douglass School dating back to 1925 as well as photos of the classrooms, the school, its teachers, and its students. Despite the hand-me-down textbooks, ill-equipped chemistry labs, and the lack of dependable school buses, former students remember the school as a nurturing environment with dedicated teachers committed to high achievement and good citizenship.

DESPITE THE HAND-ME-DOWN TEXTBOOKS, ILL-EQUIPPED CHEMISTRY LABS, AND THE LACK OF DEPENDABLE SCHOOL BUSES, FORMER STUDENTS REMEMBER THE SCHOOL AS A NURTURING ENVIRONMENT WITH DEDICATED TEACHERS COMMITTED TO HIGH ACHIEVEMENT AND GOOD CITIZENSHIP

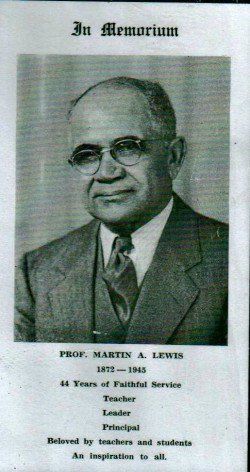

In its day, Douglass School could boast of having one of the finest school programs in the state. The school created innovative programs that the white schools would later imitate, including a manual training program, penmanship classes, and a strong musical education program. Martin Lewis, an 1893 Douglass School graduate, later became a teacher then principal at the school. He also committed himself to the development of a school band. This band, the only one in Missouri at the time, soon became the envy of the state. Today, Lewis is recognized as the Father of School Bands in Missouri.

During its 81 years of operation, Douglass High School proudly graduated 679 students. Many of these students returned as teachers and solid community leaders.

Douglass High School closed in 1955 when a federal mandate ordered the desegregation of Public School Systems. Overcrowding and lack of facilities slowed full integration until a new junior high school could be opened in 1959. Former students who lived through desegregation recall the most disheartening aspect of the process was having to leave the dedicated teachers they had come to love and respect at Douglass School. None of their former instructors were hired to teach at Hannibal's integrated high school.

EARLY 1930'S DHS BAND