Slave Narratives

An important part of hannibal's black history was saved by the wpa's effort to gather narratives from surviving ex-slaves in the 1930's via the federal writer's project. Many former slaves lived and died here in hannibal and are buried in old baptist cemetery. Meet some of those ex-slaves below.

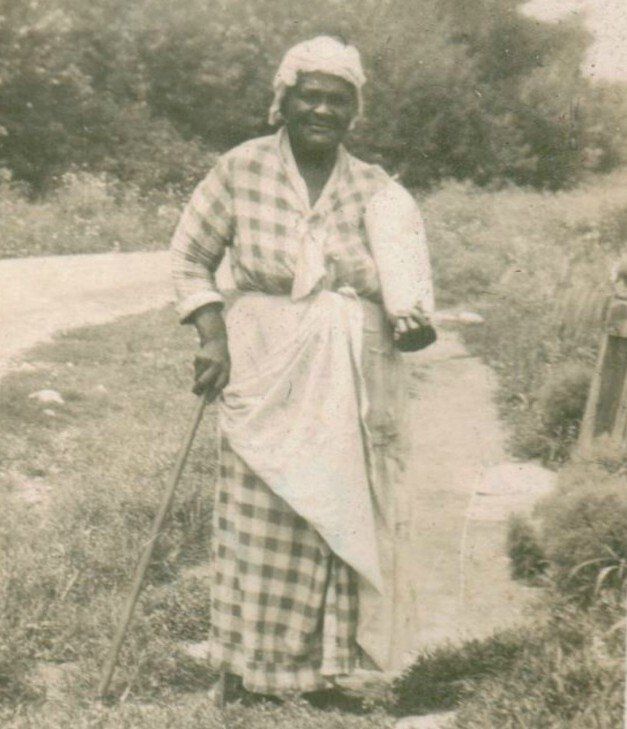

Emma Knight

Emma Knight grew up a slave on the farm of Will and Emily Ely, near Florida, Missouri. The Elys owned five slaves: Emma; her mother, Lulu, who had been brought to Missouri from a farm in Virginia; her father; and two sisters. The Knight girls and women cooked, cleaned, did laundry, and nursed babies for the Elys. Emma recalled that her master, Will, was kinder to the slaves than his wife, who regularly reminded them that they would be caught and killed if they attempted to run away. As children, Knight and her sisters

"cut weeds along de fences, pulled weeds in de garden and helped de mistress with de hoeing. We had to feed de stock, sheep, hogs, and calves, because de young masters wouldn't do de work. In de evenings we was made to knit a finger width and if we missed a stitch would have to pull all the yarn out and do it over."

Like most slave owners, the Elys provided their slaves with clothing only once a year. The rest of the year, Knight and her sisters made do with the cast-off clothing of the Ely children. Knight explained,

"We didn't have hardly no clothes and most of de time dey was just rags. We went barefoot until it got real cold. Our feet would crack open from de cold and bleed.

PHOTO: EMMA KNIGHT

We would sit down and bawl and cry because it hurt so. Mother made moccasins for our feet from old pants. Late in de fall master would go to Hannibal or Palmyra and bring us shoes and clothes. We got dem things only once a year. I had to wear de young master's overalls for underwear and linseys for a dress."

To make matters worse, the Elys sold Knight's father because they "wanted money to buy something for de house," showing the same level of concern for this little family as they did for an old piece of furniture.

Once emancipation came, Knight and her mother and sisters sought to leave the Ely farm but were convinced to stay when Will Ely promised them "a couple hundred dollars" if they would continue working there. Though they stayed awhile, they never received any compensation.

After leaving the Elys, Knight married a man named William when she was around twenty years old or less. She first show up in the Hannibal 1881 City Directory working as a servant living on 9th street. The 1909 City Directory lists her as a dressmaker. In her slave narrative, she said nothing of her husband but mentioned one daughter, who died, and a grandson, who was living with her in Hannibal. Her living space was modest, but she proudly proclaimed, "This little old shack belongs to me." Located on 928 North Street, Knight lived in one of Hannibal's oldest colored neighborhoods, Douglassville. Her child and grandchild may have attended the segregated Douglassville School. She regularly attended Hannibal's oldest colored church, the Eighth and Center Street Baptist Church. When Knight died in 1945, she was buried with most former slaves in the Old Baptist Cemetery.

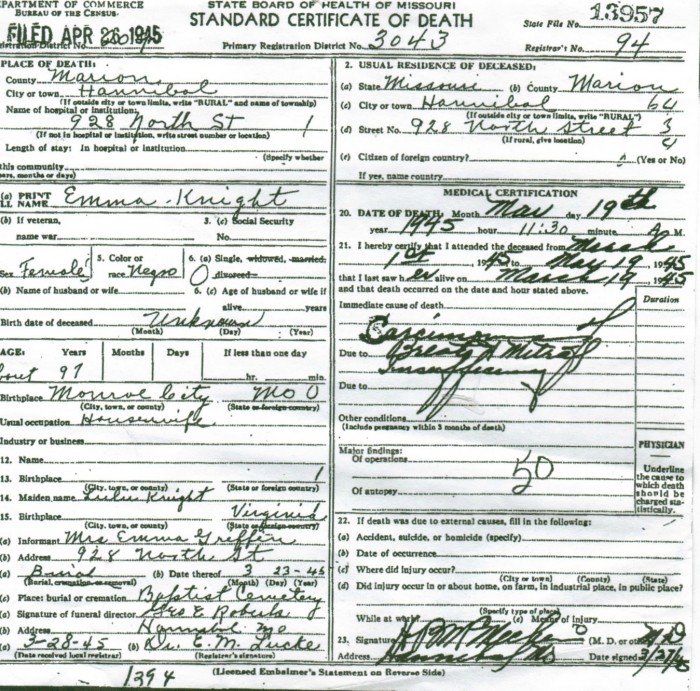

KNIGHT'S DEATH CERTIFICATE

Lewis Mundy

At the time his slave narrative was recorded by the WPA, Lewis Mundy had been living with his daughter on West Center Street in Hannibal for thirty years. Though the year of his birth is unknown, he was born a slave on John Wright's farm north of La Belle, in Lewis County. Wright owned eleven slaves total, Mundy's mother and her ten children. The Wrights has brought Mundy's mother to Missouri from Virginia with them. Billy Graves, the Wrights' adjoining neighbor, owned Mundy's father.

Mundy stated that "[o]ur master and mistress was good to us," but his follow up that "my own mother had to whip me often" suggests a different story. It may be that the Wrights truly were good to their slaves, but the fact that they gave the Mundy family nothing after emancipation, unlike neighboring slave owners who provided their slaves with land, implies otherwise. The Wrights might have required Mundy's mother to punish him, rather than doing it themselves. Perhaps Mundy hesitated to tell the white employee of the WPA about the true cruelty of his former masters. Whatever the case. Mundy's words leave it unclear.

Even as a young child, Mundy worked. "When I was small," he recalled, "I rode one of de oxen and harrowed de fields. When I was about ten or eleven I plowed with oxen." In another enigmatic description that seems to state one thing while implying the opposite, Mundy says,

"We never wanted for clothes very bad. We wore long shirts dat reached to de knees until we was twelve or fourteen years old. Dem wool shirts sure was warm. We had one pair of shoes a year. Many times I done went after de cows barefoot when dere was more dan a foot of snow on de ground."

Despite his claim that the Wrights provided their slaves with sufficient clothing, Mundy relates his experiences of going barefoot in the snow and suffering from the heat in his cheap wool shirt, facts that contradict his initial claim and tell an alternative story of his life in slavery.

After emancipation, Mundy moved with his mother to Newark. He married at twenty and moved to Jetto. Mundy worked as a farm laborer to support his wife and two children, one of whom died young. In 1903, Mundy and his family settled in Hannibal, where he worked for seventeen years until he grew too old and retired with a pension. Like other African Americans in Hannibal, church community played an important role in Mundy's life.

NO KNOWN PHOTOS OF LEWIS MUNDY EXIST.

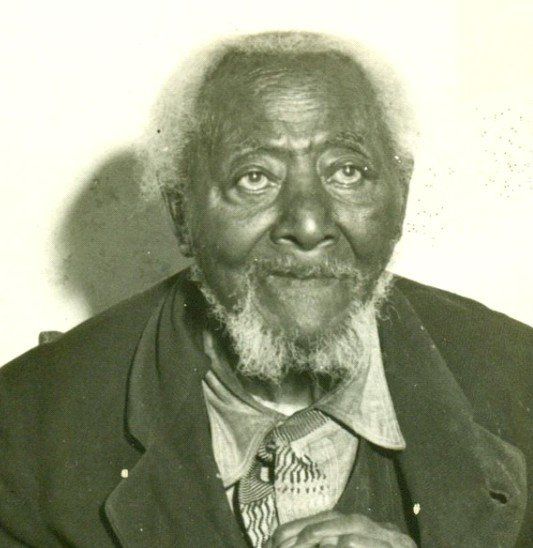

Henry Dant

Born in Saline County, Missouri in 1835, Henry Dant served as a slave on Judge Daniel Kendrick's farm south of Monroe City in Ralls County until the end of the Civil War brought emancipation. His parents, Joe and Sue Dant, were brought to Missouri by the Kendricks before Henry and his siblings were born. In his slave narrative, collected by the WPA, Henry recounts, "We worked hard on de farm. I cradled wheat and plowed corn often till midnight. We often drove hogs to Palmyra and Hannibal." After his brother died, Henry "was de only colored man on de place," leaving him with a heavy workload. Despite his long hours of slave labor, Mr. Dant still found time to work for the betterment of his family:

"I played a fiddle for all de weddings and parties in de neighborhood. Dey paid me fifteen or twenty cents each time and I had money in my pockets all de time."

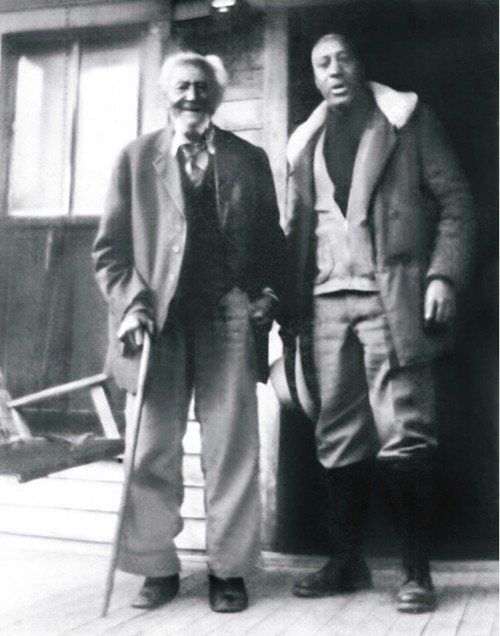

HENRY DANT, 1936

This type of work may have helped support Mr. Dant, his wife, and three children after slavery ended. As Henry recalls, "When we was set free dey gave us a side of meat and a bushel of meal. Dat's all we got." Mr. Dant became a farmer after his emancipation, moving to Marion County where he lived with his oldest son, Charlie Dant.

When he grew too old to farm, Henry moved to Hannibal where he lived with his oldest daughter, Evaline Dant Quisenberry, until he died in 1939. In Hannibal's African American community, one found men and women who supported each other and encouraged their children to excel despite barriers of racial segregation. One of Dant's granddaughters, Elle Belle Dant Hobbs, had graduated from the segregated Douglass School, where she taught for the next forty years. Henry Dant died in 1939, living to be 103 years old. His WPA account of his experience in slavery is featured in the Hannibal Courier Post Circa 1937, the Missouri Historical Society, and the Library of Congress.

Dant's descendants continue to reside in Hannibal and make significant contributions to the black community. Faye Dant, the wife of Henry's descendant Joel Dant, a fifth generation Missouri resident, has preserved Henry Dant's story as an integral part of Hannibal's African American history through her efforts as Executive Director of the Jim's Journey museum.

PHOTO:

HENRY AND OLDEST SON, CHARLES DANT, PHOTO CIRCA 1925